“You need to talk to him,” the hospice nurse was saying. “You need to give him permission to die.”

“You need to talk to him,” the hospice nurse was saying. “You need to give him permission to die.”

It wasn’t the first time she had told me this over the last couple of days, but I wasn’t exactly itching to do whatever it was she was suggesting.

“Sometimes, for reasons that are unclear, people in their last days hold onto life against all reason,” she explained. “You need to tell him it’s OK to go.”

For 10 days my father had lingered, refusing all food or liquid, the very final stages for many Alzheimer’s patients who simply forget how to chew, how to swallow, how to live any longer.

My mother sat not more than 10 feet away from him, trapped, amazingly, by the same hideous disease, thoroughly unaware she was soon to be widowed. Neither of them acknowledged each other anymore, but a couple of weeks earlier, my father had suddenly called out, “Where’s Francine?” perhaps a sign, the hospice people said, that in the deep recesses of his mind he was worried about leaving her.

And so he had to be told it was OK to die. And somehow, I was going to be the one to tell him.

The youngest of four children by seven years, I was the classic daddy’s girl, hopelessly spoiled by his affection, the one you could find on most nights cuddled up on the couch with him, styling his hair or giving him a foot rub.

“How do we even know he can hear us?” I asked.

Like our mother, he had been on a steady decline with Alzheimer’s for more than two decades. But for the last week or so, he had sat in a rented hospital recliner with his eyes half open and his head buried in his chest, no obvious signs that anything at all was getting through.

“Even if it’s not in his head but in his soul, he will hear you,” the nurse promised. “We can leave the room if you want.”

I glanced around, looking for a possible escape route, but all I saw was our den, as we called it growing up. There was the same couch—though twice reupholstered from the gaudy orange vinyl some hippie decorator thought was a good idea in 1970—where my father let me run wet combs through his hair in rousing games of beauty shop. It was now where we situated my mom, a place she had probably never sat for more than two minutes my entire childhood. The TV was turned to some random station she never would have watched, and on top of the coffee table sat a hospice pamphlet, a box of Kleenex, and some latex gloves in a heap she never would have allowed.

I had no plan, nor any useful experience to fall back on before speaking such seemingly important words to my father. I rambled a bit and repeated myself. But as I sat on the arm of the recliner, my head leaning against his head, he ever-so-slightly turned a warm cheek toward mine, and somehow, I knew that he did hear me.

“I’m going to miss you, Dad,” I whispered in his ear. “I’m going to miss someone worrying about me the way you always have and loving me the way only you could. But I promise we’ll be OK. I promise we’ll never forget you. Every time I look into my children’s blue eyes, I will be reminded of you.

“We love you, Dad. And it’s OK. You did your job. You did a fantastic job. You can rest now. I promise we’ll take care of Mom for you.”

I got up shakily and looked over at my mother, suddenly realizing I had barely spoken to her over the past year. Sure, we visited, and I held her hand and told her I loved her. Then I’d say goodbye.

Hello. I love you. Goodbye. Ever since she had stopped speaking, I had as well.

And so I talked to her, too. “I told Dad,” I said, holding her hand. “I don’t know if he heard me. You know he was never a great listener. But I told him we’ll all be OK.”

Alzheimer’s patients in the late stages seldom look people in the eye. My mother’s gaze had been at an off-angle for years. But as I spoke the next words, she looked directly at me, so much so that it stunned me for a second before I continued.

“I’m supposed to go to this 25th reunion at Niles West for our state championship team tonight,” I told her. “Can you believe it? I’m going to see Connie. And maybe even Peggy. You remember Peggy, Mom. And Barb and Tina and Holly, and Judy Becker and Karen Wikstrom. Remember, Mom? Remember how great it was? And Mr. Earl will be there, too.”

I looked closely to see if there was any kind of a flicker at the mention of our coach, Gene Earl. I thought maybe I saw one. “Yeah, well, I think it’s probably time to move on, don’t you?” I laughed softly, hoping I could keep her attention. But she went away as quickly as she had returned.

What the hell I was even thinking, running off to my old high school after an afternoon as wrenching as this one, I did not know. But after that night, I no longer wondered.

I had finished high school on the highest of highs after our team had captured the state basketball title, but personally, I was through. I was ready to move on, still somewhat bitter about my decreased playing time under a new coach and wanting very much to embrace college life, find a boyfriend, and leave behind my tomboy ways. And since then, frankly, I hadn’t been all that interested—as my mom used to call it—in taking a walk down nostalgia lane.

And then Connie called.

Connie Erickson was the star of our team, and though she was one of my closest friends in high school, we had drifted apart. Over the last 25 years, we had only occasionally spoken, but she phoned from her home in North Carolina that week to ask if I was going to the reunion.

“If you’re going, I’m getting a plane ticket right now and coming in,” she said.

She told me she had read a column of mine online, the one I had written about us for the Chicago Tribune, and she needed to reconnect with us. She needed to come home.

When I walked into the Niles West gym that night, I immediately locked on the faces of parents so familiar to me during my teenage years that they may as well have been my own. They looked immediately beyond me, searching expectantly for my parents. I explained as delicately as I could why they weren’t there and was met with a shower of hugs and expressions of sadness and told that they would be my parents that night.

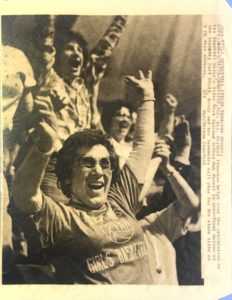

We were honored at halftime of the Niles West girls’ game, a big screen set up in front of one basket, where a highlight reel of our accomplishments was shown. And later, we ended up at the home of Barb Atsaves, a junior starter on the championship team. She played the video of the final game as husbands, children, parents, and significant others gathered to watch. I had wandered out of the family room, still absorbing the events of the day, when I heard a loud cheer go up and calls for me to come back in.

For a good 20 seconds or so, the camera had scanned the crowd before settling on my parents. They were cheering madly, my mom’s bad arm thrust oddly but triumphantly above her head, both my parents so genuinely happy that I was both shocked by the sight of them that way and immediately transported back to that time.

The room grew a little quieter as I stared at the TV. And as we walked to our cars in the frigid Chicago cold a few hours later, Connie and I tried to grasp the enormity of what we had experienced, both that night and 25 years earlier.

“You have to tell our story,” she said finally, her arms wrapped tightly around her for warmth.

I nodded.

In 1979, Niles West High School won the third-ever Illinois girls’ state basketball championship. We beat future Olympic gold medalist Jackie Joyner’s East St. Louis team with a merciless full-court press and a punishing transition game.

But that’s not what Connie was talking about.

In my Tribune column, I had written about some of the things we never knew at the time. Like how our first coach, Arlene Mulder, would secretly huddle in the corner of the faculty lounge with the school’s legendary boys’ basketball coach, Billy Schnurr, and how he would teach her how to teach us. I had learned that our principal, Nicholas Mannos, like most high school principals back then very stern and a little scary, was just as secretly our best friend, for years fighting the battle for girls to attain the same rights as boys in sports.

But, as it turned out, it was more than even that.

Six days after the reunion, my father finally stopped fighting. Coach Earl, who I had not seen in at least 15 years, attended the funeral. So did several of my former teammates, and the ones who didn’t attend, called or wrote, as did their parents. Over the course of the next several months, I reconnected with them and with others who played with us over the years. I searched for Peggy, the only member of the team we couldn’t seem to locate and the one with whom I ultimately bonded the most. And I invited Becky Schnell to lunch.

“Becky, you have to tell me,” I said as I began the reporting for this book. “Was I mean to you?”

She laughed. A freshman when I was a senior the year we won the title, Becky had supplanted me in the lineup, and I wasn’t thrilled. Adding to my frustration was the knowledge that Becky lived in the Niles East district, not West’s, and as far as I could figure only played for our team because her father, a junior high physical education teacher in the area, must have pulled strings. It annoyed me at the time, and I wondered if Becky ever caught on.

“No, Missy. You were never mean to me,” she said. “Don’t you remember how much fun we had? Don’t you remember how much we laughed?”

I was relieved, but I couldn’t leave it there.

“But Becky, what was the deal with your going to Niles West?” I said.

There was a long pause. “You didn’t know?” she replied.

“No,” I said. “What?”

She leaned across the table, and I met her in the middle.

“Miss,” she told me, “basketball saved me.”

And there was our story and my start to this book. Some of it I knew, some I would find out, and some still comes to me in waves.

Over the next several months, I would pore over news clippings and whatever video and cassette tapes I could get my hands on; comb through our yearbooks; and talk to Niles West teachers, students, coaches, and administrators as well as our opponents. I would badger my teammates for their recollections, and without hesitation, they complied, handing over treasured scrapbooks held together by useless strips of Scotch tape, the very act of turning each page putting them at risk of crumbling completely. But that was just the beginning.

For the next decade, I worked and reworked the manuscript, picking it up for months and putting it down for years, struggling with doing justice to our story before ultimately falling in love with it all over again.

This story is about one group of girls sitting innocently at a monumental place in our nation’s history. But it is not a history lesson, nor a treatise on Title IX, as significant and responsible as that piece of legislation was for our being there in the first place. Rather, it is about the sheer joy of getting our first uniforms, packing the same school gym where we were once not allowed to practice, and gaining access to life lessons previously only available to boys.

It is about Mrs. Mulder, who taught us how to believe; Mr. Schnurr, who taught us how to fight; and our last coach, Gene Earl, who took a crash course in the world of girls and would never be quite the same again.

It is about a hunger so insatiable, setbacks so painful, and a triumph so sweet that it altered the course of our lives.

In the process, basketball removed us from troubled homes and sad circumstances and transformed us. It instilled confidence and gave us our very identities. We were no longer tomboys or outcasts or even normal girls with unusual interests. Suddenly and forever more, we were athletes, driven by one common goal, united for one solitary purpose.

To say that basketball changed us wouldn’t be fully accurate. In truth, I would find out, it saved us all.

View Trailer

You can order Melissa Isaacson’s new book at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bam! Books-a-Million and Indie Bound.