-

Retirement Part I

I thought it was just fatigue talking. But the weariness Michael Jordan described in late January, 1993 was more than the dog days of another NBA season. More than the weariness of defending back-to-back titles and in Michael’s case, even more than seeing his shooting percentage dip to its lowest point in the previous six seasons and his clutch ability showing some uncharacteristic chinks.

These last few weeks have allowed me, forced me at times, to read, talk and remember what happened nearly 30 years ago. Sometimes, even the smallest details come rushing back unexpectedly, like when Teddy Greenstein, an old friend from the Tribune, asked me for my recollections of Michael’s retirement press conference for a story that ran in today.

I did not remember with the clarity of longtime Chicago sportscaster Mark Giangreco, some of the details from that day. But I did flash back to months before that day.

We were in Houston, Michael was getting ready to face the trash-talking guard Vernon Maxwell and while this would normally be fun for him, he was out of sorts.

“I may just lose my temper,” he said.

The Bulls were a ragged 28-15 going into this game and in a recent loss to Orlando, Jordan had attempted 49 shots, a career-high and seven more than the rest of the starting lineup combined (I looked that part up, obviously! But I do remember that trip and that talk with Michael).

There he goes again, the grumbling began amongst some of his teammates, flashing back to the days of “Jordan and the Jordanaires.” Michael said it was just a case of trying to maintain the Bulls’ standard, which he had obviously played a major part in building. But his teammates didn’t understand that, he said that night, and he didn’t like what he was feeling.

I had gotten Michael alone in Houston’s visiting lockerroom and with no access to players the next couple of days, I was able to sit on the story until we got home, when it ran in that Sunday’s paper.

“It’s human nature that when success comes around, everybody’s fat and everybody’s independent, when before everyone was supportive and connected and tight,” Jordan had said. “All championship teams go that way.

“But that’s going to be the ultimate destruction of this team.”

But it was more than that. And it wasn’t until I spoke to him in the Birmingham Barons’ clubhouse a year later, that I realized the full extent of what had been happening.

Guys were tired, he said of that mid-season rut. They were getting treatment and sitting out and practice “lost the fun.” He had become bored.

“I knew halfway through the season, that was it,” he told me in the summer of ‘94. “I didn’t have anything left to prove. Even if we wouldn’t have won a third title, that was it. But I did want to finish off on a good note. I thought maybe my decision would help me focus a little harder, especially when the playoffs came. But the regular season was a drag for me. It was tough for me to motivate myself because I knew you don’t get anything until the playoffs.”

Jordan said he tried to tell his teammates at the time.

“And not just one night,” he said. “We’d have a couple of beers after the game and they’d be complaining about this or that, pointing fingers as they liked to do, and I’d say ‘Man, you don’t know how good you have it. You watch, I’m not going to be around here much longer. I think this is going to be my last year.’ And they’d say ‘Sure MJ, sure.’ And I’d say ‘I’m not kidding, man. I don’t think I’m going to play next year.’

“I told them all and they all shrugged it off. I kept saying it. Not once, not twice but three or four times. I could sense they didn’t believe me. ‘Sure MJ, you’re either pissed off or you’ve been drinking.’”

At the press conference announcing his retirement in Oct. of ’93, Michael said his father wanted him to consider retirement after the Bulls’ first title. After James Jordan was shot and killed that summer, it became that much clearer. In his heart, Michael didn’t want to play another game of basketball if his father wasn’t around to see it (it was the reason he changed to his high school No. 45 for a short time when he came back. His dad had seen his last game as No. 23, he reasoned).

Bulls coach Phil Jackson had asked him if he wanted to take a year off to find himself again. A sabbatical, like a college professor. But Michael didn’t want to move on with “loose ends,” he said. And in the months after his retirement, he found joy in unusual places. For an entire day, he told me, he rode around Chicago on a motorcycle, something his Bulls contract had forbidden him to do.

That winter, he and a group of family and friends went to Aspen on a four-day ski trip, Jordan giggling as he described starting on the “bunny hill” and then finally progressing to the blue (intermediate) runs.

“My scariest adventure was the same day I learned the hockey stop,” he recalled. “I’m coming down the hill headed straight for this tree. I couldn’t do the snowplow. The only way I could stop was to do the hockey stop. It was the greatest. I loved it. From that point on, I knew I could do it. I enjoyed it immensely. It was a lot of fun.”

Well, except for one thing.

“I fell about 10 times [off the chairlift],” he said. “I’d get off too late most of the time. And just as I got off, the next chair would come around and whooomph, push me down.”

Michael has always had a great laugh. It’s infectious and when he gets going, as he was this time, he was gasping for breath as he was telling the story. “I looked like a yard sale – skis here, poles there,” he gasped. “I’d come around and yell ‘Look out below, I’m going to wipe someone out.’

“It was beautiful and quiet, but here’s this big, tall black guy on skis. It was pretty tough to hide. Then again, it was just as tough for anyone to bother me as I was flying around.”

He loved the solitude. But he loved basketball more. The first time he started going to the Berto Center again was early in the ’93-’94 season, not long after his retirement announcement, ostensibly just to visit. He hadn’t planned on playing as he stood and watched, but Jackson complained the team looked terrible.

“No continuity, no rhythm, no nothing,” Michael remembered Phil grumbling.

Jordan couldn’t help himself, he said.

“I said, ‘Do you mind if I come in and try to get some competition back into practice, just to get them flowing somehow?’”

“I don’t know,” Phil replied. “We’ll see.”

Already, there were rumors that this was just a break from basketball and that Jordan would be back at the end of the season. “Never say never,” he had answered when asked if he would ever consider it, and he had to convince Phil that wasn’t his intention.

It didn’t take much convincing and after a quick drive back home to get his shorts and a shirt since his locker had been cleaned out, Jordan was back on the Bulls practice court.

Jackson told the team Michael was going to practice and “Right then,” Jordan recalled, “I could sense the competition. Scottie and Horace started talking shit: ‘If you’re on the red [non-starting] team, you’re going to get treated like it.’ And I’m like OK, maybe I can help this team. These were the guys [newcomers like Toni Kukoc, Steve Kerr, Pete Myers and Bill Wennington] who didn’t know the offense, so I had to do a little more.

“I wasn’t in shape, my wind was short, but I could still do certain things.”

One of the first things was to get Kukoc involved. Pippen was guarding him tough and suddenly Michael was Toni’s protector, baiting Scottie to move over and guard him instead.

“So he’d make a basket and talk some shit and I’d make a basket and say ‘I retired myself, nobody retired me.’ So we’re going back and forth and it was great. That was the atmosphere that I remembered, and I think they kind of forgot.”

By then, almost immediately after announcing his retirement, Jordan had started frequenting Comiskey Park. He’d get there by 8:30-9 every morning and be out by noon, he said, sneaking through the empty TV entrance and parking his car out of sight, just in case.

“I wanted to be able to walk away without anybody knowing, in case I didn’t have the skills to play,” he said later in Birmingham. “But I loved it and that’s when I really developed an appetite for the game.”

Baseball had been a bond between father and son. They watched Atlanta Braves games together when Michael was growing up because that was the closest team to them, but James loved Roberto Clemente, the legendary rightfielder for the Pirates and so Michael did as well, playing rightfield for the Double-A Barons.

When I interviewed him in Birmingham in July of 1994, it was approaching the one-year anniversary of his father’s murder and what would have been James’ 58th birthday.

The trial had not yet been scheduled but Michael knew he wouldn’t be there.

“The damage has been done,” he said. “Whatever they do to those guys is not enough. So I’ve blocked it off. My father died because of something stupid, and I won’t let that hurt me again by going through it again. Justice may prevail, but there’s no justice when there’s no life.”

While his family sought closure, “to me,” Michael said, “the end was when he was taken.”

“I keep him alive with what I’m doing,” he said, then motioned to the locker stall beside his. “I feel him standing next to me all the time. It’s hard to explain, but I just know he’s close by.”

I started and stopped this blog a bunch of times over the last week because I never knew how and when to end it. I wrote about him still wearing his Carolina blue shorts under his uniform as he always did under his Bulls uniform. And about how he played pick-up basketball on beaches and in parks, games that would start like any other and end with crowds ringing the court as people came running as soon as word got out.

I wrote about the sincere affection I felt his Barons’ teammates had for him. One player, outfielder Scott Tedder, a Division III basketball player, wore the same size baseball cleats – 13 – as Michael, and thus was the beneficiary of dozens of shoes that Jordan gave him. Several other players shared a new Mustang, which Michael had been given by a local dealer but didn’t need. Jordan would also help the Barons find a $350,000 bus and he paid the lease so he and his team could travel around the Southern League in style.

Another player, Rogelio Nunez, a back-up catcher from the Dominican Republic, had been trying to learn English when his new teammate came up with an idea. Every day, Michael would give Nunez a word related to baseball and if Nunez spelled it correctly, Michael gave him $100.

Like I said, I didn’t know how to end. So I’ll do it here, awkwardly. Maybe I’ll pick it up when he came back to basketball. Not sure yet. Waiting for those memories to come rushing back again.

-

Riding on Air again

Melissa Isaacson, Tribune staff reporter CHICAGO TRIBUNE

May 1, 2005 FONTANA | CALF.

His favorite time was always 10 at night until 3 in the morning, when the streets were quiet and the summer air cool and he could open it up a little.

Well, a lot.

He rode during the day, too, sometimes with his nephews but more often alone, hiding beneath his helmet and cruising through the city, enjoying the solitude and reliving his youth, when he and his brothers would jump ditches and pop wheelies and try to keep their more risky dirt-bike escapades from their mother.

One summer day two years ago he ended up downtown, at the BP station across from the Rock ‘n’ Roll McDonald’s on LaSalle and Ontario, where bikers seemed to congregate and, oddly, no one rushed him when he dismounted his Ducati and took off his helmet.

Off-duty Chicago cop and motorcycle enthusiast Noble Williams saw Michael Jordan get off his bike, but more than that he saw a guy in a nylon jogging suit and Air Jordans.

“I saw him come in and I walked over to him and said, `You’re doing this all wrong,'” Williams recalls. “He kind of looked at me like, `Who the heck are you?’ I said, `You need to wear jeans out here and you need a jacket and gloves and some boots.’ Then I gave him my card and said, `If you want to ride tomorrow, we’ll ride, but you need to get this equipment.’

“He called next day and we rode and had a good time.”

Suddenly, Michael Jordan was in his element, with guys who liked speed and control and could teach him some things. Before he knew it, he was introduced to a talented young black rider, Montez Stewart, who taught him how to ride, how to really ride, and took him to a track where he could learn how to corner and downshift and look for his points of reference.

Two years later, the young man is on the Jordan Suzuki racing team and Jordan is a player in the American Motorcycle Association. And on this day, a gorgeous Saturday in the shadow of the San Bernardino Mountains, one of the greatest players to grace a basketball court is in all his glory at the California Speedway.

Dallas and Houston have just grinded their way to an exciting finish in the NBA playoffs, but as far as Jordan is concerned, a first-round series can’t touch the AMA Superbike Championship, where reigning champion Matt Mladin blew his clutch and Ben Spies edged out Aaron Yates in the last lap.

Jordan’s rider, Steve Rapp, finished eighth, a good result considering he was the top racer among the non-factory teams.

Above the Speedway, with a cigar in one hand and a Corona in the other, Michael Jordan lets out a whoop as Rapp whizzes by.

No pep talks needed

This is not a guy who looks like he is bored or misses basketball. He talks to Bulls general manager John Paxson on a fairly regular basis, and has frequent conversations with Ben Gordon. But when the question of pep talks to his former team comes up, the man who is as closely associated with victory as any athlete in history knew he couldn’t win.

“If I’m around, I’m stealing the spotlight, and if I’m not I’m deserting them,” Jordan says. “They’re doing a great job. Why would I go and interfere now? No one gave us a pep talk. They have a different makeup, this team. The city is happy and I’m happy. But now that they’re winning, I’m not going to say, `Wait, I’ll come in and give you a pep talk.’

“Pax tells me I’m welcome and I appreciate that. But I’m so busy. Ben calls me and I tell him, `Relax, give a pump fake once in a while.’ He’s a great kid. But most fans have moved on. The kids remember me more from `Space Jam.’ And I’m as close as I want to be to the game. I’m enjoying my life, I’m enjoying my kids. I’m not bothering anybody. I go to Cubs games and Sox games. I’m not sure what else anyone wants me to do.”

He’ll show up at a second-round game, he says, confident the Bulls will prevail over Washington. If he is not scarred by his experience in Washington, where he was effectively fired before he could resume his role as the Wizards‘ president of basketball operations, he was clearly wounded.

“I’m mad at myself more than anything,” Jordan says of the experience. “At the end of the day, my biggest mistake was going down and playing again [for the Wizards for two years]. I thought it would help me evaluate talent better for when I went back upstairs, but in doing that I put trust in someone who I shouldn’t have and that’s the most disappointing thing. I’m not sure how anyone can say I failed them when they were $35 million in debt when I got there and profitable two years later.

“But I’ve gotten over it and moved on. I still talk to some of the players and I’ve learned from the whole experience.”

He is content now, he says, and it doesn’t take a hard sell to believe him. Earlier Saturday he’d gone down to Turn 1 so he could see the riders close up, where the scream of their engines is loudest and you can see their knees scrape the track. Jordan’s smile brightens as he leans against the fence and absorbs the vibration.

“Man, I’m hooked,” he says. “I wish they had 20 races a year [rather than a dozen], that’s how much I love it. It’s amazing how I missed this so long.”

Fascinated by speed

He grew up a NASCAR fan. His father James was a Richard Petty guy and he would take his children to Rockingham and Talladega and Charlotte, his youngest son transfixed by the speed and the sounds and the danger, and he’d go home and get his fix jumping dirt bikes around their home in Wilmington, N.C.

At North Carolina, coach Dean Smith would have killed him if he got near a motorcycle, and once he signed with the Bulls his contract prohibited any dangerous activities. His next time on a bike was after his first retirement from the Bulls in ’94, when he bought a BMW Cruiser. In ’98 he got on again and has rarely been off since.

The racing team began as a rather simple pursuit, supporting Montez Stewart. “I could tell it was his dream,” Jordan says, “and I said, `Let’s see what I can do for him.'”

In February 2004 they debuted Jordan’s team with Stewart as the only rider. Today, with the collaboration of Clear Channel (which bought out AFX, Jordan’s management group), Suzuki and Gemini Racing, Jordan’s team has three riders, Rapp and Jason Pridmore having joined Stewart. And with Jordan’s leverage, sponsors like Gatorade, Upper Deck and Oakley have come on board, companies not associated with the sport before.

“Nobody took us seriously at first,” said James Casmay, Jordan Suzuki’s business manager, a former amateur racer who first met Jordan at the BP. “One of the only companies who would sponsor us at first was a leather-goods company. But what people saw right away and what allows average guys like us get to know and work with him is that we’re all sharing a passion.”

After some initial skepticism, Jordan impressed people with his genuine interest and desire to learn the sport. “I wasn’t sure if his goal was to sell more clothing and shoes or to win races,” says Kenny Abbott, general manager of Jordan Suzuki. “But it’s clear he wants to be competitive, and with his exposure and his help I think we’ve already changed this industry.”

Jordan is the only African-American owner and Stewart one of a few black racers, and the team hopes it can reach a broader demographic. “If you look on the street, there are a lot of black guys riding motorcycles,” Jordan says.

Abbott believes the Jordan name has already made a difference. “I’ve been involved with this sport since 1987 and not until last year did I see people showing up at the racetrack in head-to-toe [Jordan] racing gear,” he says.

Jordan is contractually committed to racing through 2006, but he doesn’t see his association ending then, even if he accomplishes his goal of owning an NBA team.

“So far there’s nothing close, but I’m still investigating,” he says. “I have the capital, but if I’m going to pay $375 million, can I make money and can it sustain itself? Once I see a situation where it can, I’ll jump into it. But I don’t see getting out of this. I want to continue to grow this.”

One of the biggest upsides to Jordan’s investment in competitive racing–an $850,000 investment last year–is the opportunity to grow his Jordan brand of shoes and apparel, as he has done in boxing with Roy Jones Jr. and in baseball with Derek Jeter. To that end, based on Jordan’s suggestion, the team has changed its colors each year, from Carolina blue in 2004 to this year’s strange combination of black, red and yellow.

“When Nike first came to me with the black and red shoes, I said, `I’m not wearing that,'” Jordan recalls with a laugh. “And when I told these guys my idea, they said, `It looks like the bikes have been pieced together with spare parts.’ But that’s what I like about it. It’s wild. Nobody else ever changes. If you look in the paddock, we’re who everyone comes to see.”

His involvement with his team is a daily matter and it covers all areas, including the actual racing. “We have a lot of conversations,” he says of his relationship with his riders. “If they’re not confident on the track, they’re more susceptible to injury. I try to give the mental preparation for battle.”

Says Rapp: “He’s very involved. He’s pretty laid-back but he wants to know everything–how the bikes are running, how the tires are doing, what the lap times are like. He likes to know what’s going on.”

Tries to keep low profile

Down in pit road, Jordan is just another guy, but when he ventures into the paddock there are fans and sponsors and friends of sponsors and there is invariably a small mob.

He signs autographs and poses for pictures but generally tries to keep as low a profile as possible. “He really wants to keep the focus on the team,” says Abbott. “He honestly believes his time was in the NBA and this is their arena, their time to shine. He really just wants to learn the industry inside and out.”

He has become one of its biggest salesmen. “This is so much more exciting than auto racing,” he says. “Unlike NASCAR, you can see the drivers. The races are shorter. It’s not like sitting in the stands watching for three hours.”

His sons Jeffrey, 16, and Marcus, 14, both ride dirt bikes as well as excel at basketball, and their father shakes his head as he talks about what they’re doing to his lawn.

Despite the objections of his longtime friend and assistant George Koehler, who was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident while riding with a friend 10 years ago, Jordan clearly loves riding. He confines his riding to the track these days and has been clocked at 170 m.p.h.

He regularly attends Jason Pridmore’s racing school, though Pridmore, who finished third at Daytona in March, was injured in a race last weekend in Birmingham and just released from the hospital after surgery to remove his spleen and repair a lacerated kidney. Jordan himself has totaled three bikes but has never suffered anything more serious than some scrapes. “It’s still a lot safer than riding around the city,” he says.

Still a taut 228 pounds, Jordan marvels at the hand-eye coordination of the racers. “These are top athletes, make no mistake,” he says. “I live vicariously through these guys.”

His Carolina blue bike travels with the team, and Jordan goes to almost every race.

Now he climbs on, puts on his helmet, pulls on his gloves and zips up his leather jacket. He is wearing jeans. But some habits are tough to break–he is also wearing Air Jordans.

He pops a wheelie. And with a wave and a smile, he is gone.

-

Tourneys cancelled, payoff to come

The announcement Tuesday was just another drop of bad news in a virtual flood this last month

or however long it has been now. It’s hard to keep up, both with the days and the news. And

when the Illinois High School Association said it was officially cancelling all spring sports state

tournaments, it was no surprise, an inevitable response to Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s earlier decision to

close state schools for the rest of the academic year.But this one still hurt. And like the decisions to cancel proms and graduations and some of the

winter state tournaments, the sting will be felt acutely and linger for a while.As someone who has experienced the very best high school sports had to offer, and 40 years later

is still talking about it, what I am going to say next might sound like the kind of consolation

parents have tried to offer heartbroken kids through the ages and received cold stares and tears in

return.I’m going to say it anyway.

But first I’m going to tell you about IHSA Executive Director Craig Anderson. It was his name

and statement on the press release about the cancelled state tournaments. But he is no bureaucrat.

I had met him previously and liked him instantly. And when I spoke to him Tuesday, he was as

down as anyone.“I stir and stir over these types of decisions and feel for every athlete not getting an opportunity

they have likely dreamed of … and my heart aches making the decision not to recognize multiple

state champions and state qualifiers, and every level of success we won’t have.”He paused.

“Hopefully, they will see, if not now than in the future, all the benefits they’ve had and life

lessons they’ve learned. It’s all we can hope for at this point.”Before you think it’s easy for him to say, Anderson has three sons, the two younger ones, three-

sport athletes in high school. Tucker, 21, is now finishing his junior year at Monmouth College

and wondering what his senior football season is going to look like. Mac, 16, missed his

sophomore baseball season at Morton High School in Central Illinois.“It hits home for sure,” Anderson said.

At the end of “State,” the book I wrote about my 1979 Niles West High School girls’ basketball

team, we win the state championship. But I tell you that in the prologue. Heck, I tell you that on

the jacket cover and in the title. In our case, I also tell you that our story is not about basketball

as much as it is about the innocence of being part of the first generation of Title IX girls and how

it changed us forever.But the lessons we learned about winning and losing, about leading and following, about making

mistakes and learning from them, about triumph sure, but also about heartbreak, didn’t dawn on

us then because it never does.I tell people it is a coming-of-age story and you don’t have to win a state championship or even

play in a state tournament to get that. We all come of age at a certain point. Being part of a team

doesn’t make it happen any quicker but in high school, it makes it easier to pinpoint later on.It is when you learned about sacrificing for the good of the group. Or that when you were a jerk

and selfish and got told off by teammates or even kicked off the team, there were consequences.

Maybe it’s when you learned you could be a real leader. Or that not everyone can lead but

following well is an important trait too.It is in their teenage years that many athletes experience for the first time what it means to push

themselves beyond what they thought was their limits. Others learn that they’re not ready yet –

not for this pursuit, not at this time but maybe they learn what it looks like close up.If you happen to be one of the gifted ones and you weren’t particularly conscious of the plight of

the kid at the end of the bench, or maybe you weren’t even particularly kind, you might realize

this at some point. But it probably won’t happen in high school.None of it will.

More than likely it will happen when you encounter a boss who reminds you of the coach who

used to make you run extra laps and you figured out how to get in his or her good graces. Or

maybe it happens when you have to do a group project at work and you fall into the role of the

good team member without even knowing where you picked it up.Maybe that self-esteem you gained the first time you accomplished the goal of trimming your

time in cross country comes in handy during that big presentation. Or you don’t escalate that

argument with your new spouse because you’re a team now, and somehow, somewhere, in some

way you learned what that means.The meeting Tuesday in which they made the decision to cancel state tournaments was not done

with a proverbial rubber stamp and it ran long as IHSA board members agonized over how to

recognize senior athletes in ways befitting their athletic careers. Just trying to figure out a way to

make it special.“I understand,” Anderson said sadly, “about the lifetime memories they’re not getting now.”

He felt badly because we all do. For different reasons. Today, it’s for the kids who won’t get to

compete for the ultimate trophy. But he also talked about what high school athletes

have learned well before these last many weeks.“Even if they don’t get the chance to compete again at the high school level,” Anderson said,

“they are better for having been a part of their respective high school teams.”At some point, they’ll realize it. Just not today.

-

Some things I remember

They came with their camera crew last spring, bearing glad tidings and detailed questions that made me very nervous because although I remember my years covering the Bulls for the Chicago Tribune very fondly, my recall for details like the terms of Scottie Pippen’s second contract are somewhat sketchy.

The director Jason Hehir and his coordinating producer Jake Rogal could not have been nicer or more patient as I scoured my memory for tidbits they might want to include in their upcoming documentary “The Last Dance.” But what I wanted to say was, “If you ask me about Will Perdue’s shoes or Horace Grant’s aversion to mice or that time Michael threw up, I’m here for you.”

So, as a service to those who care about such things and as reassurance to myself that I haven’t lost it completely, here are a few things I do recall from that incredible time:

I remember Ron Harper teasing B.J. Armstrong after B.J. had glanced at me one day and suddenly noticed I was in a late stage of pregnancy, then proclaimed that he could never be present for a childbirth, that it was gory and icky (not sure he used the word “icky” though) and that he would pass out for sure.

Harper and I tried to convince B.J. that this was perfectly natural thing and not gross at all (though at this stage, I should point out I had no direct evidence of this).

In a matter of minutes, Harper had his teammate lay down on a training table in the tiny visiting dressing room (don’t ask me which one, they were all tiny back then) and coached B.J. (playing the part of birthing mother) through a simulated childbirth. Somewhere in there, I threw in some breathing techniques I had picked up along the way and soon, a basketball (playing the part of new baby) was born.

It was actually very realistic and very serious and we almost had B.J. converted to the wonders of Lamaze, when Phil Jackson walked into the room to, I can only assume, address his team before the game, took one look at this scene, shook his head and walked back out.

I remember the hundreds of pregame meals in media cafeterias, and sitting near the Bulls’ coaches’ table so I could watch the routine that would invariably ensue with the dignified Johnny Bach, the ex-Marine, sitting ramrod straight and staring disapprovingly at fellow assistant Tex Winter as Tex gratefully and happily wolfed down his food.

“Peasant food,” Johnny would sniff as Phil would prod Tex in much the same way Mikey’s brothers did in getting him to eat the Life Cereal.

“Aren’t you going to try that green stuff, Tex?” Phil would tease. “It looks good, go ahead, try it.”

I remember the practical jokes usually levelled at the nearest rookie like Corey Blount, who came to expect one atomic substance or another in his underwear. But Horace Grant was a favorite target and Scottie Pippen was usually the perpetrator, once tying a rubber mouse to Horace’s boxers and watching in sheer glee, his hand clapped over his mouth, as his 6-foot-10, 235-pound buddy and the team’s power forward shrieked and tippy-toed around the locker room in fear.

I remember current events working their way into the locker room like every other office, the John and Lorena Bobbitt story drawing special attention. Most pushed the death penalty for the woman accused of severing her husband’s penis while he was asleep in bed.

Of course, the merits of Lorena’s case and the abuse she had endured at the hands of her husband had not yet been hashed out, and indeed she would be found not guilty by reason of insanity. But the case was quickly tried in men’s locker rooms everywhere, the Bulls’ included. And it was pretty clear where they stood.

“She must be punished,” said a gravelly voice in the corner of the room, Bill Cartwright speaking slowly and ever so seriously. “Oh yes. She must be punished.”

I remember Cartwright’s face as he saw me in a hotel hallway coming out of another player’s room, where I had been doing an interview for my book.

“Don’t ever do that,” he intoned.

“Do what?” I replied.

“Don’t go into a man’s hotel room,” he said.

“But it’s Steve Kerr,” I said incredulously of one of the kindest and biggest gentlemen I have ever known.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Cartwright. “If the other guys saw that, you know what they’d think.”

He was right. And I didn’t do that again.

And speaking of very tall men, I remember being on the same flight once as the Washington Bullets.Yes, they flew domestic like real people. Even more incredible is that they put their 7-7 center Gheorghe Muresan in coach.

But the best part is that right after we landed, no sooner had the flight attendant yelled at us not to get up until the plane came to a full stop, Gheorghe reached up, opened the overheard compartment and pulled out his stuff – all from a seated position.

Truly worth the price of the ticket.

Tall people II: I remember picking up Bulls rookie Toni Kukoc and taking him to the lakefront, near the Planetarium, where Tribune photographer Chuck Cherney would do a photoshoot to accompany a story I was writing.

What I hadn’t thought through is that I was driving a Cutlass Calais, a compact, and Toni was 6-foot-11. Luckily he was either too polite or his English may not have included the words he wanted to call me, but he folded his legs into the compartment where regular-sized legs usually went, for the 45-minute ride, while I prayed I did not permanently maim the newest Bulls star and personal favorite of general manager Jerry Krause.

Like most sportswriters, I remember all the holidays on the road, particularly Thanksgivings when I covered the team during their West Coast/Texas Triangle swing each November.

Specifically, I remember one year in Portland and our stay in an elegant but small European-styled hotel called The Benson. Walking through the lobby after checking in, I ran into the Bulls GM, who motioned to a corner of the lobby and doors to the dining room, clearly closed off to the general public.

“That’s a team-only dinner, no media allowed,” Krause said, maybe just relaying the information but probably also concerned I might force my way in.

With Mike Mulligan and Kent McDill, the team’s other full-time beat writers from the Sun-Times and Daily Herald, respectively, off to other dinners, I was alone in my room when the phone rang.

“Phil asked me to call and tell you to join us for dinner,” said then-head trainer Chip Schaefer.

I suspected Phil knew Jerry had barred me and this was one more way to annoy the GM he loved annoying. Either way, I was thrilled for the company, even my very quiet little table of Kukoc, whose English at that point was still a work in progress, and trainer John Ligmanowski.

And I tried not to look in the direction of Krause.

Johnny Ligs was responsible for one of my big “scoops” with the team and I say this only partially sarcastically. It was Johnny, whom I spotted late one afternoon in the darkened Berto Center, where the Bulls trained, as I cracked open the training room door to see if any players were still around and instead, spotted Johnny sewing a new No. 45 onto Michael’s jersey.

We had no idea Michael was returning from his first retirement not as No. 23 but 45.

“Can I write that for tomorrow?” I half-asked, half-pleaded. “Off the record.” (Hopefully the statute of limitations on my promise has expired).

He relented and I wrote a very small blurb because I’m not sure editors believed me. Today, it would be a Twitter sensation and I might have more than 2,143 followers.

I remember Will Perdue lending me one of his size-22 Nikes to bail me out for a speech I was giving. Unaccustomed to public speaking and unprepared for a school Career Day, I spied Will and his enormous shoes as I was leaving the Bulls practice facility one day and begged the young center to help me out.

“So you want my shoe as a prop?” he asked.

“Well … yeah,” I responded cleverly.

Of course, he agreed because Will is one of the nicer human beings around, and it worked. I put the shoe on the podium the next day – and would use it again in future speeches. Just stuck the red and white u-boat in front of the audience and oohs, ahhs and laughter would ensue, making it impossible to hear or remember anything I said.

Unfortunately, he wouldn’t let me keep it.

I remember one road trip when there was a tattoo convention at the team hotel, and a woman happily handing over her tattoo gun to Phil, presumably not a professional, and asking him to tattoo his signature on her stomach. He didn’t. I don’t think.

I remember pregames with Cartwright sipping coffee and Phil doing the N.Y Times crossword puzzle and visiting players coming around and asking for Michael’s autograph like it was the most natural thing in the world.

I remember Don Calhoun, the 23-year-old Bulls fan from Central Illinois who won $1 million for swishing a 79-foot shot during a third-quarter timeout. But what I remember was not the shot but the reaction of the Bulls players on the bench, enveloping him in hugs and high-fives and admitting to having trouble concentrating on the game afterward they were so excited.

Calhoun wore J.C. Penney-brand gym shoes, made five bucks an hour as an office supply clerk and was nervous about celebrating so hard he’d be late for his 8 a.m. shift the next morning.

“I looked over,” he said afterward, “and the Bulls were pulling for me all the way, especially Horace. I could see it in his eyes.”

I never doubted it. Horace was like that.

“It took me three years to make a million dollars,” he joked afterward. “It took him five seconds.”

I also remember Walter Owens, a liquor porter for Bismarck Catering who struck up a friendship with Michael, chatting and joking and wrestling before games in Chicago Stadium and then, at Michael’s behest, sticking his head into the Bulls’ pregame huddle outside their locker room at the bottom of the steps leading up to the court – Walter, at 5-foot-4, on the third step so he could peer in. It became a superstition and Michael wouldn’t let Cliff Levingston yell “What time is it?” and the rest of the team yell “Game time” until Walter was in position.

After the Bulls won their second title, after the initial champagne-pouring and on-court celebration had begun to wane, team owner Jerry Reinsdorf and Jerry Krause, along with Phil and Michael and Scottie and Horace gathering briefly in the tiny officials’ dressing room to light some cigars and make a private toast. Walter was peeking in and a security guard started to shoo him away when Pippen piped up, “He’s family. He doesn’t go anywhere.”

“And so there,” as I wrote in my book, “beneath the court in which they had triumphed and later danced; behind doors that no one even knew about; in the relative sanctuary of quiet though joyous reflection; the principal parties of the NBA champions gathered for a private photo – Reinsdorf and Krause and Jackson and Jordan and Pippen and Grant … and Walter, of course, kneeling right in the middle and holding the Larry O’Brien Trophy.”

Of all my memories, that second championship in ’92 stands out most.

The Bulls had come back from a 17-point deficit to Portland late in the third quarter. We were on an incredibly tight deadline for a championship game, and I remember I had only a few minutes to file my story after the final buzzer. I would have a later deadline in which to smooth things out, get quotes, add color. But I didn’t want to wait for the final deadline, not when every suburb, including my parents’, got the first-edition Trib, and I wasn’t the best at making deadline concessions.

It was the Bulls’ first title at home, the only one at the old Stadium, and I needed to soak it in. And so I did. And it nearly killed me. Initially, I was happy with my decision, standing in the middle of the court, scribbling away in my notepad as I watched the happy scene unfold.

The team then headed down the narrow steps, just off the baseline, to accept the trophy. I followed, not wanting to miss anything and I was one of a handful of regular media who had a special designation on my press pass that would allow me into the presentation. But by that time, a couple hundred or so others had joined me on court and I was pinned against the boards next to the stairs. I remember thinking this would be a hell of an excuse to blow deadline, getting suffocated and all, but also thinking maybe they’d extend it for me if I eventually was resuscitated.

I survived and somehow made my way down to the room they were using for their postgame celebration. It was there, smashed into a tiny rectangular space that was oddly deemed the most appropriate place for a trophy presentation, that I squeezed in close enough to hear Jackson address his team — “Great job, fellas,” — and to see them nod back.

They recited the Lord’s Prayer, then showered each other in champagne, the blood on Pippen’s jersey blurring, then turning pink. And if I ever entertained the thought that this might be a cool moment to experience as the champagne engulfed me, the feeling of burning acid searing my eyes and temporarily blinding me quickly told me otherwise.

And then I was chasing them again.

“Grab that trophy and let’s show it to them,” Phil yelled as they headed back up the steps.

“Let’s go,” Michael commanded and they fell in line as always.

Clutching my now-damp notepad and realizing I had badly missed deadline, I wondered if I had made a selfish decision trying to insert myself into the middle of the mayhem, when Michael jumped up onto the scorers’ table and beckoned his teammates to join him.

“And then,” I wrote frantically, “there were all of them. Together. Doing a giant line dance on top of the scorers table. Right in the middle of the bedlam. Linking arms and singing and toasting the crowd. Milking it all and soaking it up. Every last bit of it.”

That, I remember.

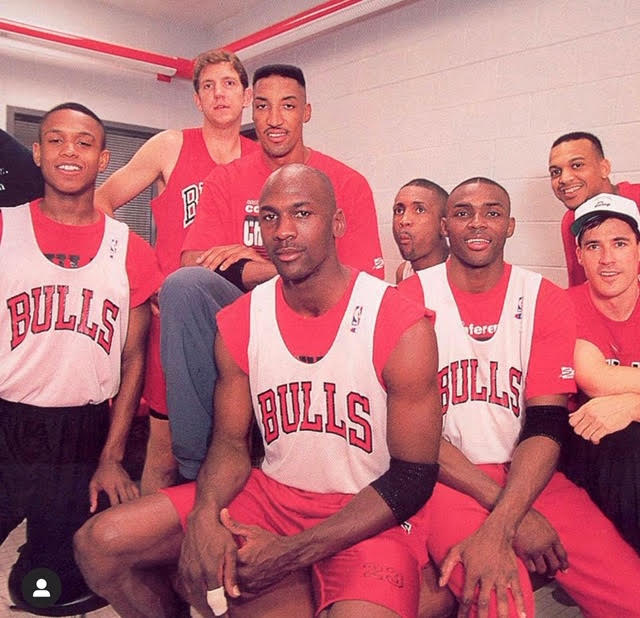

Photo courtesy of Scott Williams, who had no idea who took it but I’m guessing it is the magnificent Bulls photographer Bill Smith

-

Giving voice

Angling for a little attention in a world where worthwhile causes are as prevalent as iphones, the quiet battle being waged by a group of Chicago-area women is much more important than it may appear.

Nearly 50 years after Title IX gave girls the legal right to compete on the same proverbial playing field as boys, there are far fewer women who are coaching them. In Illinois this 2019-2020 season, 76 percent of girls’ high school basketball teams are coached by men.

Forget for now the very real argument that women should be considered on every level for boys’ and men’s coaching jobs. That’s the ultimate goal, of course. But first things first.

“The big thing with us is that we felt excluded in our own game, on the outside looking in and it’s not good for the girls to see that,” said Cara Doyle, in her eighth year coaching the girls’ team at St. Ignatius.

And so Doyle, New Trier coach Teri Rodgers, Glenbard West coach Kristi Faulkner and Ashley Luke, formerly the coach at Mother McAuley and now guiding the girls’ team at Norcross High in the Atlanta area, decided they’d do something to let people know.

This weekend at Glenbard West, the inaugural Grow the Game tournament and Shootout is “highlighting” 14 girls’ basketball programs led by female head coaches. They want to celebrate girls and women in basketball, they say. But it’s more than that, said Rodgers

“I think across the board, girls and women need to know they have a voice,” Rodgers said. “For a young girl to be in a relationship and know she has a voice in that relationship. Then going into the workforce, to know they have a voice and they need to be listened to.”

With fewer women coaches acting as ready role models, it’s not easy. So what happened to the women coaches?

The wave of men coaching girls’ teams began in the 70s, when male athletic directors thought men were their best candidates and men stopped looking at it as an insult and realized it wasn’t a career-killer.

“From a societal point of view, any profession that becomes popular and more profitable, [this happens],” Rodgers said.

Rodgers, who has more than 500 wins in her 22 years as the Trevians coach, was a multi-sport athlete and All-State basketball player at Libertyville who went on to play at Duke. All but one of the women coaches at the Grow the Game tournament played for Division I college programs, with three – Luke, Marist’s Mary Pat Connelly and Zion-Benton’s Tonya Johnson – also playing professionally in the WNBA or overseas.

Rodgers, who currently has two former players now competing at Notre Dame, called it an “incredible moment” five years ago, when she coached against one of her former players. “That was a dream, really,” she said.

Same thing for Doyle when she had a former player coaching her freshman team. But clearly, it’s not enough.

Doyle, the mother of four kids, 12 and under, has taken it upon herself to lecture her friends and fellow moms.

“Every mom I know, so many were competitive athletes, and I tell them, ‘You’ve got to coach t-ball and third-grade soccer.’ We buy [our daughters] play kitchens and it’s gotta be the same way,” she said. “They have to see us doing this and making decisions and all the other stuff that goes into coaching. My kids [two boys and two girls] say, ‘What if we don’t want to coach?’ and I tell them, ‘Well, one of you has to.’

“My 12-year-old son wears a St. Ignatius girls’ basketball t-shirt and that’s a win right there.”

By forming their unofficial committee, Doyle, Rodgers and the others realized they could collaborate and discuss their unique issues. “Like the ref coming up to your male assistant, assuming he’s the head coach,” Rogers said. “It’s like, ‘OK, I’m not crazy if this is happening to you as well.’

“But rather than focusing on the negative stuff, we try to focus on the positives we bring and just support each other.”

They also noticed something else interesting. “One thing I realized when I talk to my team is they don’t keep score the way we do – ‘The boys’ got new uniforms’ and ‘We have to use the downstairs gym.’” Doyle said. “They don’t come in with chips on their shoulders.”

Refreshing as that may be, she said, the girls may be in for a shock.

“When they get a job, it might not be as obvious,” Doyle said, “But they may look around one day and say ‘Wait, I did all this work and I’m not getting the same opportunities.’”

All the more reason to find their voices now.