They came with their camera crew last spring, bearing glad tidings and detailed questions that made me very nervous because although I remember my years covering the Bulls for the Chicago Tribune very fondly, my recall for details like the terms of Scottie Pippen’s second contract are somewhat sketchy.

The director Jason Hehir and his coordinating producer Jake Rogal could not have been nicer or more patient as I scoured my memory for tidbits they might want to include in their upcoming documentary “The Last Dance.” But what I wanted to say was, “If you ask me about Will Perdue’s shoes or Horace Grant’s aversion to mice or that time Michael threw up, I’m here for you.”

So, as a service to those who care about such things and as reassurance to myself that I haven’t lost it completely, here are a few things I do recall from that incredible time:

I remember Ron Harper teasing B.J. Armstrong after B.J. had glanced at me one day and suddenly noticed I was in a late stage of pregnancy, then proclaimed that he could never be present for a childbirth, that it was gory and icky (not sure he used the word “icky” though) and that he would pass out for sure.

Harper and I tried to convince B.J. that this was perfectly natural thing and not gross at all (though at this stage, I should point out I had no direct evidence of this).

In a matter of minutes, Harper had his teammate lay down on a training table in the tiny visiting dressing room (don’t ask me which one, they were all tiny back then) and coached B.J. (playing the part of birthing mother) through a simulated childbirth. Somewhere in there, I threw in some breathing techniques I had picked up along the way and soon, a basketball (playing the part of new baby) was born.

It was actually very realistic and very serious and we almost had B.J. converted to the wonders of Lamaze, when Phil Jackson walked into the room to, I can only assume, address his team before the game, took one look at this scene, shook his head and walked back out.

I remember the hundreds of pregame meals in media cafeterias, and sitting near the Bulls’ coaches’ table so I could watch the routine that would invariably ensue with the dignified Johnny Bach, the ex-Marine, sitting ramrod straight and staring disapprovingly at fellow assistant Tex Winter as Tex gratefully and happily wolfed down his food.

“Peasant food,” Johnny would sniff as Phil would prod Tex in much the same way Mikey’s brothers did in getting him to eat the Life Cereal.

“Aren’t you going to try that green stuff, Tex?” Phil would tease. “It looks good, go ahead, try it.”

I remember the practical jokes usually levelled at the nearest rookie like Corey Blount, who came to expect one atomic substance or another in his underwear. But Horace Grant was a favorite target and Scottie Pippen was usually the perpetrator, once tying a rubber mouse to Horace’s boxers and watching in sheer glee, his hand clapped over his mouth, as his 6-foot-10, 235-pound buddy and the team’s power forward shrieked and tippy-toed around the locker room in fear.

I remember current events working their way into the locker room like every other office, the John and Lorena Bobbitt story drawing special attention. Most pushed the death penalty for the woman accused of severing her husband’s penis while he was asleep in bed.

Of course, the merits of Lorena’s case and the abuse she had endured at the hands of her husband had not yet been hashed out, and indeed she would be found not guilty by reason of insanity. But the case was quickly tried in men’s locker rooms everywhere, the Bulls’ included. And it was pretty clear where they stood.

“She must be punished,” said a gravelly voice in the corner of the room, Bill Cartwright speaking slowly and ever so seriously. “Oh yes. She must be punished.”

I remember Cartwright’s face as he saw me in a hotel hallway coming out of another player’s room, where I had been doing an interview for my book.

“Don’t ever do that,” he intoned.

“Do what?” I replied.

“Don’t go into a man’s hotel room,” he said.

“But it’s Steve Kerr,” I said incredulously of one of the kindest and biggest gentlemen I have ever known.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Cartwright. “If the other guys saw that, you know what they’d think.”

He was right. And I didn’t do that again.

And speaking of very tall men, I remember being on the same flight once as the Washington Bullets.Yes, they flew domestic like real people. Even more incredible is that they put their 7-7 center Gheorghe Muresan in coach.

But the best part is that right after we landed, no sooner had the flight attendant yelled at us not to get up until the plane came to a full stop, Gheorghe reached up, opened the overheard compartment and pulled out his stuff – all from a seated position.

Truly worth the price of the ticket.

Tall people II: I remember picking up Bulls rookie Toni Kukoc and taking him to the lakefront, near the Planetarium, where Tribune photographer Chuck Cherney would do a photoshoot to accompany a story I was writing.

What I hadn’t thought through is that I was driving a Cutlass Calais, a compact, and Toni was 6-foot-11. Luckily he was either too polite or his English may not have included the words he wanted to call me, but he folded his legs into the compartment where regular-sized legs usually went, for the 45-minute ride, while I prayed I did not permanently maim the newest Bulls star and personal favorite of general manager Jerry Krause.

Like most sportswriters, I remember all the holidays on the road, particularly Thanksgivings when I covered the team during their West Coast/Texas Triangle swing each November.

Specifically, I remember one year in Portland and our stay in an elegant but small European-styled hotel called The Benson. Walking through the lobby after checking in, I ran into the Bulls GM, who motioned to a corner of the lobby and doors to the dining room, clearly closed off to the general public.

“That’s a team-only dinner, no media allowed,” Krause said, maybe just relaying the information but probably also concerned I might force my way in.

With Mike Mulligan and Kent McDill, the team’s other full-time beat writers from the Sun-Times and Daily Herald, respectively, off to other dinners, I was alone in my room when the phone rang.

“Phil asked me to call and tell you to join us for dinner,” said then-head trainer Chip Schaefer.

I suspected Phil knew Jerry had barred me and this was one more way to annoy the GM he loved annoying. Either way, I was thrilled for the company, even my very quiet little table of Kukoc, whose English at that point was still a work in progress, and trainer John Ligmanowski.

And I tried not to look in the direction of Krause.

Johnny Ligs was responsible for one of my big “scoops” with the team and I say this only partially sarcastically. It was Johnny, whom I spotted late one afternoon in the darkened Berto Center, where the Bulls trained, as I cracked open the training room door to see if any players were still around and instead, spotted Johnny sewing a new No. 45 onto Michael’s jersey.

We had no idea Michael was returning from his first retirement not as No. 23 but 45.

“Can I write that for tomorrow?” I half-asked, half-pleaded. “Off the record.” (Hopefully the statute of limitations on my promise has expired).

He relented and I wrote a very small blurb because I’m not sure editors believed me. Today, it would be a Twitter sensation and I might have more than 2,143 followers.

I remember Will Perdue lending me one of his size-22 Nikes to bail me out for a speech I was giving. Unaccustomed to public speaking and unprepared for a school Career Day, I spied Will and his enormous shoes as I was leaving the Bulls practice facility one day and begged the young center to help me out.

“So you want my shoe as a prop?” he asked.

“Well … yeah,” I responded cleverly.

Of course, he agreed because Will is one of the nicer human beings around, and it worked. I put the shoe on the podium the next day – and would use it again in future speeches. Just stuck the red and white u-boat in front of the audience and oohs, ahhs and laughter would ensue, making it impossible to hear or remember anything I said.

Unfortunately, he wouldn’t let me keep it.

I remember one road trip when there was a tattoo convention at the team hotel, and a woman happily handing over her tattoo gun to Phil, presumably not a professional, and asking him to tattoo his signature on her stomach. He didn’t. I don’t think.

I remember pregames with Cartwright sipping coffee and Phil doing the N.Y Times crossword puzzle and visiting players coming around and asking for Michael’s autograph like it was the most natural thing in the world.

I remember Don Calhoun, the 23-year-old Bulls fan from Central Illinois who won $1 million for swishing a 79-foot shot during a third-quarter timeout. But what I remember was not the shot but the reaction of the Bulls players on the bench, enveloping him in hugs and high-fives and admitting to having trouble concentrating on the game afterward they were so excited.

Calhoun wore J.C. Penney-brand gym shoes, made five bucks an hour as an office supply clerk and was nervous about celebrating so hard he’d be late for his 8 a.m. shift the next morning.

“I looked over,” he said afterward, “and the Bulls were pulling for me all the way, especially Horace. I could see it in his eyes.”

I never doubted it. Horace was like that.

“It took me three years to make a million dollars,” he joked afterward. “It took him five seconds.”

I also remember Walter Owens, a liquor porter for Bismarck Catering who struck up a friendship with Michael, chatting and joking and wrestling before games in Chicago Stadium and then, at Michael’s behest, sticking his head into the Bulls’ pregame huddle outside their locker room at the bottom of the steps leading up to the court – Walter, at 5-foot-4, on the third step so he could peer in. It became a superstition and Michael wouldn’t let Cliff Levingston yell “What time is it?” and the rest of the team yell “Game time” until Walter was in position.

After the Bulls won their second title, after the initial champagne-pouring and on-court celebration had begun to wane, team owner Jerry Reinsdorf and Jerry Krause, along with Phil and Michael and Scottie and Horace gathering briefly in the tiny officials’ dressing room to light some cigars and make a private toast. Walter was peeking in and a security guard started to shoo him away when Pippen piped up, “He’s family. He doesn’t go anywhere.”

“And so there,” as I wrote in my book, “beneath the court in which they had triumphed and later danced; behind doors that no one even knew about; in the relative sanctuary of quiet though joyous reflection; the principal parties of the NBA champions gathered for a private photo – Reinsdorf and Krause and Jackson and Jordan and Pippen and Grant … and Walter, of course, kneeling right in the middle and holding the Larry O’Brien Trophy.”

Of all my memories, that second championship in ’92 stands out most.

The Bulls had come back from a 17-point deficit to Portland late in the third quarter. We were on an incredibly tight deadline for a championship game, and I remember I had only a few minutes to file my story after the final buzzer. I would have a later deadline in which to smooth things out, get quotes, add color. But I didn’t want to wait for the final deadline, not when every suburb, including my parents’, got the first-edition Trib, and I wasn’t the best at making deadline concessions.

It was the Bulls’ first title at home, the only one at the old Stadium, and I needed to soak it in. And so I did. And it nearly killed me. Initially, I was happy with my decision, standing in the middle of the court, scribbling away in my notepad as I watched the happy scene unfold.

The team then headed down the narrow steps, just off the baseline, to accept the trophy. I followed, not wanting to miss anything and I was one of a handful of regular media who had a special designation on my press pass that would allow me into the presentation. But by that time, a couple hundred or so others had joined me on court and I was pinned against the boards next to the stairs. I remember thinking this would be a hell of an excuse to blow deadline, getting suffocated and all, but also thinking maybe they’d extend it for me if I eventually was resuscitated.

I survived and somehow made my way down to the room they were using for their postgame celebration. It was there, smashed into a tiny rectangular space that was oddly deemed the most appropriate place for a trophy presentation, that I squeezed in close enough to hear Jackson address his team — “Great job, fellas,” — and to see them nod back.

They recited the Lord’s Prayer, then showered each other in champagne, the blood on Pippen’s jersey blurring, then turning pink. And if I ever entertained the thought that this might be a cool moment to experience as the champagne engulfed me, the feeling of burning acid searing my eyes and temporarily blinding me quickly told me otherwise.

And then I was chasing them again.

“Grab that trophy and let’s show it to them,” Phil yelled as they headed back up the steps.

“Let’s go,” Michael commanded and they fell in line as always.

Clutching my now-damp notepad and realizing I had badly missed deadline, I wondered if I had made a selfish decision trying to insert myself into the middle of the mayhem, when Michael jumped up onto the scorers’ table and beckoned his teammates to join him.

“And then,” I wrote frantically, “there were all of them. Together. Doing a giant line dance on top of the scorers table. Right in the middle of the bedlam. Linking arms and singing and toasting the crowd. Milking it all and soaking it up. Every last bit of it.”

That, I remember.

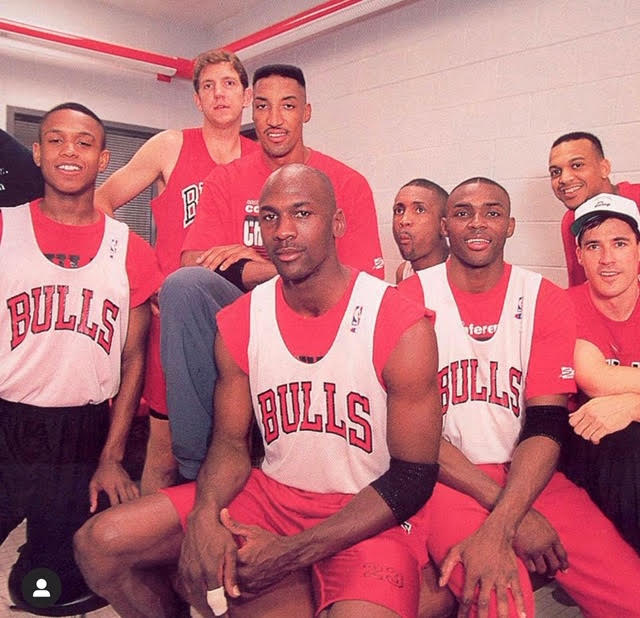

Photo courtesy of Scott Williams, who had no idea who took it but I’m guessing it is the magnificent Bulls photographer Bill Smith